News

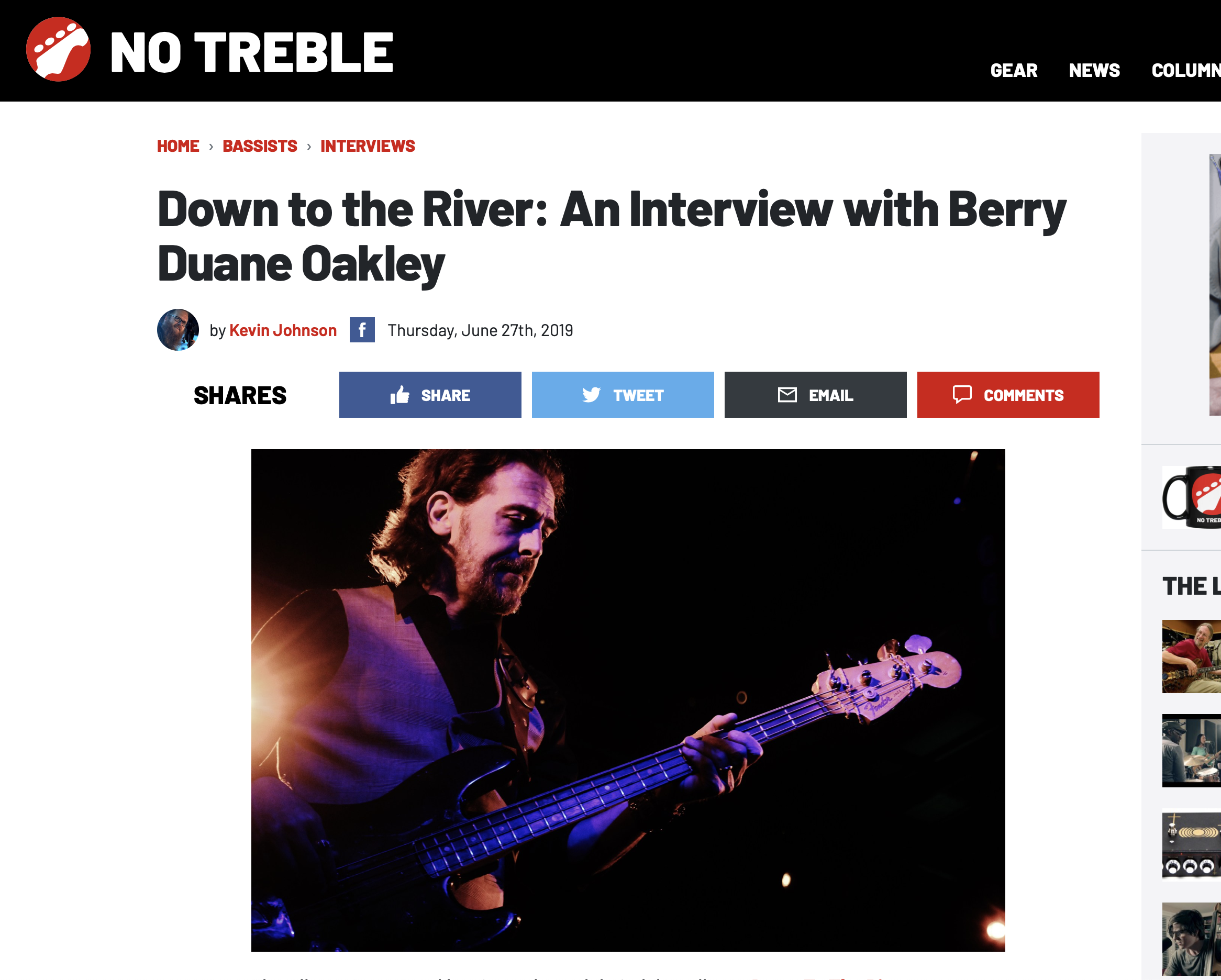

Down to the River: An Interview with Berry Duane Oakley

The Allman Betts Band has just released their debut album, Down To The River. As you might expect, the group is tied to the Allman Brothers with three members being the sons of the legendary band’s original members. Guitarists Devon Allman and Duane Betts are the sons of Gregg Allman and Dickey Betts, respectively. The third tie is Berry Duane Oakley, son of founding Allman Brothers bass icon Berry Oakley.

Together they create a sound that is not a simple homage to the music of their fathers. It’s the culmination of their own musical experiences, capturing the spirit and energy of the Allman Brothers Band’s more than anything else. A fan of classic bass players, Oakley sticks to big grooves and old school gear to pin the album together. He cites Duck Dunn and James Jamerson as his biggest influences.

Sadly, the elder Oakley died in a motorcycle accident before his son (sometimes referred to as Berry Oakley, Jr.) was born. Berry Duane Oakley did, however, grow up deeply entrenched in the music scene as his stepfather is Three Dog Night’s Chuck Negron and his godfather is The Doors guitarist Robby Krieger. Music didn’t particularly interest Oakley until his later teen years when he truly began to appreciate performing music.

Oakley honed his chops on the road with the Robby Krieger Band as well as Bloodline, a fantastic band that featured blues shredder Joe Bonamassa and the sons of other famous musicians. The group had quick success, but the label’s marketing ploy pigeonholed the group and they soon split up. His other projects include Blue Floyd, the Chuck Negron Band, and Butch Truck & The Freight Train Band. All those credits add up to make Oakley the perfect bassist for the Allman Betts Band.

We caught up with Oakley to get the scoop on the Allman Betts Band, the infamous rig he recorded with, and the details of his father’s “Tractor” bass.

You’ve known the guys in this band for a while. How close is your bond?

I’ve known Devon and Duane for the better part of 30 years. I met Duane back in ’88 and Devon in ’89. I actually used to help babysit Duane and Elijah Blue when I was living in LA. I’d go to Cher’s house and when she would run errands, I would babysit them.

Devon and I met on the road with the Allman Brothers for the ’89 Dreams tour. We’ve kept in touch and been friends ever since. Duane and I spent a lot more time together. This will be our fourth band together, so we have a lot of history over the past 30 years.

All the names carry so much history. I think people wonder if you all grew up together or if you’re coming together later in life.

Not really. We all kind of spread out. Devon was more in Corpus Christi and St. Louis, then Duane was back and forth between California and Florida. We always spent time here and there while keeping in touch, but I wouldn’t say we grew up together, so to speak. We all went on our own paths in life.

You spent a lot of your childhood in L.A., right?

Yep. I was one of the Hollywood Hills babies. About ten years ago I moved here to Florida to look for something different. Plus I just like the weather. It’s a little more tropical.

It seems like you were constantly surrounded by music and musicians, with Chuck Negron being your step-father. Have you always been playing music or is it just something your family did and you eventually jumped into it?

I fought it for a long time. It wasn’t until my mid-teens that I really started to appreciate it and get into it: probably around 16 or 17. I was your basic pain-in-the-ass kid until about that time. I would race my skateboard down Hollywood Boulevard with people yelling at me. I came into it late. When it’s just part of your everyday life, you don’t really think much of it. Chuck is my stepdad and Robby Krieger of The Doors is my godfather, so spending time with him and the Doors family reinforced that.

So yeah, it was weird. When I finally got into it in Hollywood in the ’80s, I was still finding myself and playing in some of the local crazy hair bands. It wasn’t until I went on the road with the Allman Brothers in ’89 that I found my passion and love for it all. I got more of an understanding of what the music is all about.

Your father was a huge name in this kind of music, but you weren’t in the same kind of circle of musicians that he may have been in growing up. Do you count him as one of your main influences, still?

Again, later on once I got a little older and more mature and understanding the music [he was a bigger influence]. I always knew about him and the legacy of the Allman Brothers, but just being young and naive I didn’t quite “get it” for a while it until I really got into it. Then I understood the type of player he was and what it meant. The contributions and what he did in such a short amount of time before his passing made a huge impact on the music community.

When I started diving into bass and all my bass heroes, he became one of the tops. I’m into that old school stuff: Donald “Duck” Dunn, James Jamerson, John Paul Jones, and those good old “lay it down” kind of bass players.

I can hear that in your playing.

Thank you. I try. It’s tough. I always tell the younger guys, “I know there are a million cats out there that can do the Jaco stuff and that’s awesome, but as a bass player it’s always best to learn restraint.” If you listen to those old James Brown songs, those simple bass lines made such a big impact. There’s something to be said for a good, simple, solid bass line.

I get the feeling that you’re just as happy to sit in the pocket.

Definitely. I’m always learning and I always want to keep an open mind to new things and new styles. I’ve found my niche, which is an old school sound without a lot of effects or anything like that. I’ve always stuck to that take on bass, especially in a band this big. There are seven pieces including three guitars and a keyboard. I don’t need to be up there in that register. As they say, I like to pick my battles, so I’ll just throw a little run in every once in a while. [Once I do,] the guys in the band will say, “It’s so cool that you did that!” and I’ll say, “Trust me, I’ve waited for that for hours!” [laughs] Restraint, restraint, restraint.

There are a lot of small things you do that make a song pop, too. Just a simple slide up the neck to hit the octave can tie a transition together.

It’s a lost art. The simplicity is getting lost in a lot of songs nowadays. A simple slide up to a single note can say so much more than thirty notes to a bar. For me, anyways.

What was the band’s formation like?

We’ve been talking about it for a few years. A lot of it was more about the timing of things. It’s always been tough for us under the umbrella of our fathers and the Allman Brothers Band. We’ve all been through these projects before and it can be tough because the shadow of your family’s umbrella can overshadow anything you’re trying to do. For instance, when I was in Bloodline with Joe Bonamassa in the early ’90s, it went really well but it didn’t last long. Everyone was so focused on me, and Miles Davis’s son was the drummer, Robby Krieger’s son was the guitar player, and Joe being the prodigy he was, it just overshadowed anything we were trying to do as a band. It made it tough for us as a band to really lock.

That’s not happening here, which is really nice. We know where we come from, we know the legacy, and we all love it, of course. We love our fathers and what they’ve done, so we’ve found a way for us that makes us happy to pay our respects. I know a lot of people thought we were going to come out and just play a bunch of Allman tunes in honor of the 50th anniversary of the band. But we’ve all been trying to make our own mark on the world. We’re making a happy blend of the songs we like and our new original material while paying homage to our fathers. So far it’s been working out really great. We’ve had a great response.

It’s tough with new music, too. We’re getting a lot of Allman fans, but fortunately, everyone is receiving us really well. We still get the occasional yelling out for “Whipping Post,” though. [laughs]

How often do you oblige that?

We haven’t actually played that yet. We did it last year at the big family revival that we do every year at the Fillmore in San Francisco. That was the last time we did that. We had Marcus King there, so we had him sing it. There are a few songs we mixed into our set just depending on how we’re feeling that night.

Speaking of singing, I wasn’t really aware of Bloodline before this and it was a great band. I was impressed with your singing as well as your bass playing. Are you going to be singing with the Allman Betts Band?

Between me, Devon and Duane, we’re all singers and frontmen. I’ve been singing and leading bands for decades. I fell into singing on accident. After the Dreams tour, I started jamming around town with bands. My godfather, Robby Krieger, hired me and his son to play with him in the Robby Krieger Band. On every other show, Robby would have me sing a different Doors song. By the end of the year, I was singing about 80 percent of the Doors songs plus playing bass.

The same thing happened with Bloodline. We had a few potential guys including Sammy Hagar’s son to be the lead singer. Lo and behold, the whole band ganged up on me and said, “Berry sings. Let’s just make him the singer!” I’m grateful for that because it’s pushed me a long way. Then I had the Blue Floyd project with Allen Woody, Johnny Neel, Matt Abts, and Marc Ford. They were all singers, but nobody wanted to learn all the lyrics so they said, “Well, Berry can sing most of the tunes.”

Coming into this new project, it’s a little strange not singing that much. I’m doing backgrounds and they’re bringing me up front more and more. I’m singing about two songs per set. We’re trying to find a balance. Between the three of us, we have such unique voices. I lean more towards the blues and soul, Devon is more rock and roll, and Duane has that country thing. It’s nice taking turns. I’ll probably start taking on more tunes as it goes on.

What was the writing process like for the new album?

A lot of it was already done before I jumped in on the project. They had been working on some songs. When the time went to get into Muscle Shoals, they had a lot of the material laid out. I kind of missed out on that part of the first album, but this next record I’m going to be more involved with as far as writing and singing. Fortunately, it all worked out. It’s a strange thing because a band usually rehearses for months before they come into the studio to record. We came in there cold. I hadn’t heard half of those songs in my life. They said, “Here are the songs. They’re gonna hit the red button, so let’s figure it out.”

In a way, it was nice to get that raw perspective that got caught on tape. We’re already planning the second record, getting our songs and ideas together.

Did recording in Muscle Shoals carry any weight for you?

It was very cool. Just walking in there, you could feel the vibes and energy. It was very calm and serene. God, it’s such a tiny room, too! You see all the pictures in documentaries, but you get struck by what they could do with what they had. It just goes to show that sometimes you just need a little room with good energy. Everybody walked in with great respect for the room and its history. We just embraced it and used it to our advantage.

I know you like old school gear, so what did you use to record the album?

I actually got to use David Hood’s old bass rig that was in there. That was pretty cool. It was a Fender 300, I think. Whichever one he’s had there for decades and decades. I brought my vintage ’66 Jazz Bass. It really gave me that old school tone I was looking for.

I really loved the groove to “Down to the River.”

Yeah, that was a lot of fun. I was trying to lean towards a Duck Dunn kind of thing. Just keep accentuate the notes and keep it as simple as possible. Even though I didn’t know a lot of these tunes, they let me have my way with them. I always play to the drummer, so once I knew what kind of groove it was, I had free range to find my space in the song. That one, in particular, I could tell it was a cool, greasy feel.

Do you have a method for locking in with drummers or do you follow your gut?

For me, I follow my gut. As we bass players know, you’re only as good as your drummer. When you’re locking down on that groove with your drummer, you have to work with them – not against them. I’ve seen a lot of guys who fight their drummers, playing-wise, instead of falling in line with them. Fortunately, I’ve had a great career and gotten to play with some really cool drummers that have taught me a lot.

The same thing happened with, John Lum, the drummer for this band. I hadn’t really known him before the project. I knew him for about a year before I got involved. I got to see how he would play things. Now we’ve found a good groove together and a good way to lock. I’m more of an aggressive bass player, for sure, so I’m not standing in the back being quiet. I tend to push at times. As long as you have a good relationship it works really well.

I’ve gotten to play with a lot of great drummers: Matt Abts, Butch Trucks, Cody Dickinson… I could go on and on. You play a little differently with each drummer. For instance, if I play “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” with Cody Dickinson or Matt Abts, it will be totally different because of their styles. I just have to lock in with them.

When I was touring with the Butch Trucks Band, a lot of my dad’s bass playing made so much more sense to me. After all these years, the pieces fell into place because that was his drummer. I know so many bass players who would ask how my dad played different things and I’d give explanations, but I didn’t realize until I played in a band with Butch that it was because of his drummer. His drummer gave him that energy and space to do it. It kind of messes it up for other people because I’ll say, “Well, Butch did this, so if you do it then I can do that.” [laughs]

It’s hard for anyone that wants to play like your father did because you need a Butch Trucks on your side.

Exactly. A lot of those early Allman lines, it was Butch and Jaimoe that made them what they were. It gave my dad and the guys the space to be wacky like they were. Dickie Betts always told me, “We never had a bass player. We had two little guitars and one big one.”

He started on guitar, didn’t he?

Yeah, he did play guitar. I do as well. He fell into bass somewhere and history was made.

You have his Tractor bass, don’t you? Are you using it much?

Yeah, I do. I use it every now and then. It’s just tough now with touring because I get so nervous about traveling with it. We don’t have a huge crew still. I’ll bring it out for specific gigs and big events.

It’s a really cool bass. The main gist of it is that it’s a ’62 Jazz that he took the neck pickup out of and mounted it behind the bridge pickup. He left the bridge pickup intact and putting the neck pickup next to the bridge made it sound interesting. Then he ripped apart one of those Guild Starfire basses and took the BiSonic pickup and put it in the neck position. Then he added an extra volume and tone knob to that.

When I was hanging around with the Brothers for a long time, I got to know Joe Dan Petty, who was the guitar tech from the beginning to just about his passing. He was the one who helped my dad actually build the thing. So it was good to get how things went down from the horse’s mouth. Really, a lot of the Tractor came from my dad and Phil Lesh being close and talking shop whenever they got together. My dad just got tired of always hearing about Phil’s cool new bass features like sending each string to a different amp. That was kind of the inspiration to make the Tractor. He thought, “I’m in a big touring band and I need a crazy sounding bass that can do a lot of things, too.” One night, he and Joe Dan Petty got drunk at The Barn in Macon, Georgia and just started ripping them all apart. It’s really interesting, too. If you take off the pickguard where that BiSonic is, you can tell they literally just chiseled out the wood. It looks like they used a flathead screwdriver and a hammer to get that pickup in there. It’s pretty wild.

He’d swap necks all the time. I hear it from fans all the time: the picture has this or that. As a lot of people did with Fenders, my dad would swap the necks a bunch. The last one he put on it was the neck from a ’65 he had with block inlays. That’s what sits on it now, but I do have his other bass which is a ’65 with a ’62 neck on it. It used to be in the Hall of Fame in Cleveland but I was able to acquire it again.

You’ll be on the road for most of the rest of the year. Is there anything you can share about the next Allman Betts album?

There are some cool tunes that everyone’s bringing to the table. We’ll work it out, but it’s really in the early phases of it. I’m really curious to see how it all fits together when we hit the studio again, which should be sometime in December. I’m hoping between now and then we’ll have some pretty neat stuff. Photo Credits: Chris Brush @ Smoking Monkey Photo

Allman Betts Band Tour Dates:

| Date | Location | Venue |

|---|---|---|

| Jul 8 | Ocean City, NJ | NJ Music Pier |

| Jul 23 | Cologne, GER | Kantine |

| Jul 24 | Amsterdam, NL | Paradiso |

| Jul 20 | Maidstone, UK | Ramblin’ Man Fair |

| Jul 25-28 | Scranton, PA | Peach Music Festival |

| Jul 25-28 | Breitenbach, GER | Burg Herzberg festival |

| Aug 10 | Duluth, MN | Bayfront Blues Festival |

| Aug 11 | Fargo, ND The Hall | Fargo Brewing Co. |

| Aug 22-25 | Arrington, VA | LOCKN’ Festival |

| Aug 29 | St. Charles, IL | The Arcada Theater |

| Aug 30 | Fort Wayne, IN | Sweetwater Performance Pavilion |

| Sep 1 | Lakeville, PA | Cove Ent Resorts |

| Sep 5-8 | Las Vegas, NV | Big Blues Bender |

| Sep 13 | Colo Springs, CO | Pikes Peak Center |

| Nov 1 | Auburn, AL | Jay and Susie Gouge Performing Arts Center |